By Patty Tascarella – Senior Reporter, Pittsburgh Business Times

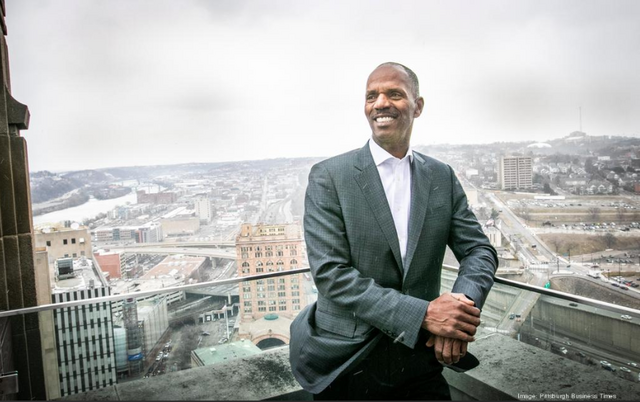

David Motley launched the African American Directors Forum, an initiative to increase board appointments at public companies.

This article originally appeared in the Pittsburgh Business Times. Click here to view.

The Rooney Rule, the 17-year-old National Football League policy requiring teams to interview minority candidates for head coach and general manager posts, is one of the most cited and copied models as the business world seeks to hire diverse employees.

The Pittsburgh connection can’t be missed, Rooney being the family that owns the Pittsburgh Steelers. But the city, with a small black population of about 8 percent, falls behind when it comes to implementing its homegrown rule — there's a comparatively low number of black professionals in leadership jobs at local public companies.

Lonie Haynes, chief diversity officer at Highmark Health, an African American recruited to the region seven years ago, is addressing this challenge head-on when he says the most prominent thing the insurance giant has done to advance its minority hiring was its recent twist on the Rooney Rule.

“We’ve rolled out Rooney Rule + Plus,” Haynes said.

Instead of making sure at least one candidate for a post is diverse, Highmark Health has doubled that.

“We’re asking for two or more,” Haynes said. “The more diversity you have on the slate, the better the opportunity is to hire someone from a diverse background.”

Efforts by Pittsburgh-area companies to attract a diverse workforce, including for leadership positions, are intensifying as they launch and augment multipronged initiatives that embrace both recruitment from outside the region and tracks to build talent pipelines that go early into the local school systems. But it is evolving, and there are no easy solutions or routes.

On March 19, the Business Times is presenting “Prioritizing Inclusion,” a luncheon event at the Fairmont Pittsburgh. John Wallace Jr., the David E. Epperson endowed chair at the University of Pittsburgh, is to deliver the keynote speech. He also is senior fellow for research and community engagement at the Center on Race and Social Problems at Pitt.

“Pittsburgh historically has not had a large, white-collar, black middle class compared to Atlanta, Detroit, Chicago, Charlotte, Dallas and Houston,” Wallace said. “The average African American income here is $26,000. … This is 2020, and we’re just beginning to have conversations at this late date. When people have opportunities, do you want to play pioneer when you can go elsewhere and enjoy a higher quality of life?”

Haynes is moderating a panel that will discuss strategies Pittsburgh companies are using to attract and retain more black professionals and executives. The scheduled panelists include David Motley, CEO and president, MCAPS LLC; Steven Malnight, president and CEO, Duquesne Light Co.; Gregory Spencer, president and CEO, Randall Industries LLC; and Tracey McCants Lewis with the Pittsburgh Penguins.

A supporting framework

While there are still challenges to creating a more diverse workforce in the Pittsburgh region, the supporting framework of programs and initiatives throughout the region is accelerating.

Wallace and several others cited the efforts of the Executive Leadership Academy, which the corporate sector, city officials and Carnegie Mellon University launched in 2018 to improve and build the regional presence of African Americans in corporate and nonprofit leadership roles. In 2019, the Advanced Leadership Initiative, a program designed to provide tools and training to increase the visibility and success of high-performing African Americans, debuted at CMU.

Motley and his wife a few years ago launched the African American Directors Forum, an initiative to increase board appointments at public companies, first locally, then taking the event to Atlanta and Palo Alto, California, with Columbus, Ohio, soon to come.

“The larger companies by default have more seats to fill and therefore can play a bigger role,” Motley said.

Motley believes a telling metric isn’t how diverse your current organization is, but how diverse was the latest cohort of new hires over the past six to 12 months.

“More and more companies have stopped accepting, ‘We looked but could not find women/minorities/African Americans,’” Motley said.

Still, he pointed out, in a market where “talent in general and diverse talent in particular have lots of options,” the unemployment rate is low, and the war for talent is real.

“Trying to get people to say yes to not just the job but a job in Pittsburgh is that much more challenging,” Motley said. “You’re not just competing with another company; you’re competing with other cities like Washington, D.C.; Charlotte (North Carolina) and Atlanta.”

So it takes a multi-layered process that starts in the school system and extends to the top of corporate governance.

“A number of the African American directors on Pittsburgh boards are not from Pittsburgh and that’s true in general,” Motley explained. “The appointments onto public company boards tend to take advantage of the national pool of talent as opposed to the local pool.”

Thomas Flannery, managing partner at Boyden Executive Search, has teamed with Motley to recruit talent, and has also attended AADF events, which he views as an important component for greater diversity in the region’s corporate sector because it includes African Americans at the governance levels.

“It’s amazing,” Flannery said. “I went to (one of the AADF events in 2019) and there were several hundred African Americans there who can serve on a public or private company board, the whole nine yards.”

Developing pools of talent

While Flannery believes corporations are “doing their best” to recruit, that’s only part of the process.

“The thing that has to happen is people have to be promoted into positions where they can climb to senior management levels from middle-management levels, and that’s hard to do if the local population doesn’t have the talent pool," he said. "It’s easy for us. We recruit from all over the world. But if a company is looking for a mid-level manager, someone making $75,000, $85,000 a year, they’re probably not going to Cleveland or Baltimore to get them. They’ll try to find them here.”

Spencer, an executive at United States Steel Corp. and EQT Corp. before acquiring now-15 employee Randall in 2006, believes it’s important for large companies to develop talent pools, enabling them to capitalize on internal candidates for, say, anticipated retirements.

“It should be an opportunity to look at where you project a position opening in the near future and the pool,” he said. “Unfortunately, what happens is a position becomes available, and they’ll do a search or advertise. That takes time and may not be aligned with the goals or timetable of applicants.”

Recruiting far and wide

At Covestro LLC, outreach and connectivity is key.

“Most companies do not understand the importance of not only making connections and leveraging relationships, but truly developing relationships with professional organizations and individuals within them who can provide support,” said Dina Clark, head of diversity and inclusion, North America. “So much of where people work or chose to apply depends on how they’ll be supported. I’m sick of hearing companies say they can’t find us. But they may not know where to turn.”

Given Covestro’s focus on industrial science, engineering and manufacturing, it makes sure to connect to industry organizations.

One of Covestro's 12 employee resource groups in Pittsburgh, Covestro ACCESS, focuses on developing African American professionals. The resource groups work with the recruiting teams, raising awareness around barriers.

“If you’re a smaller company, to me, the core of this is about identifying, developing and leveraging relationships and the talent that’s there,” Clark said. “People don’t talk enough about leveraging in inclusion and diversity.”

Covestro has internship and training pools. It works with schools, k-12, as well as colleges and universities, and its reach includes entry level, mid-level, seasoned mid-level, people in line for c-suite and community relations.

“If you don’t hit all of these areas, you’re going to miss talent,” Clark said.

The pipeline, she emphasized, must connect to larger inclusion. If not, all the company will do is create different silos.

“You can’t do recruiting without retention hand-in-hand,” she added. “Recruiting can get people to the door. You can’t keep people without the culture. If they don’t feel connected, have a voice or have a place, then you have a business problem.”

Highmark also partners with outside organizations and institutions, some of which it supports with grants, scholarships, after-school mentoring and training, to build diverse talent from within Pittsburgh.

“Those students within those programs work with us for summer programs, and the goal is to hire them, either undergraduate or post-graduate school,” Haynes said. “Part of our pipeline is working with secondary schools and learning and training institutions.”

However, part of the effort also involves recruiting talent from outside the region. When Haynes moved from Atlanta to join Highmark, he’d done his research on the city as well as the company.

“Pittsburgh has one of the least diverse populations in the country,” he said. “It’s not like the city has a rich resource of talent to pull from, as opposed to Philadelphia or Cleveland. It’s incumbent for us in the business community to cast that net for talent as far and wide as we can. That means being very intentional about going after groups ... that weren’t a first thought for us.”

He tells candidates considering jobs in Pittsburgh that they have an advantage here over, say, Cleveland, Ohio, where African Americans account for about 30 percent of the population.

“It’s a real opportunity for you to shine and be a standout, be recognized and do some really important work,” Haynes said. “I didn’t realize it when I first came here, but it’s a plus.”