This article was originally published by Directors & Boards magazine - please click here to view.

Is your board as diverse as you think it is?

Increasing diversity now seems to be at the forefront of organizational and boardroom consciousness around the globe, and for good reason. According to The Leadership Quarterly, boards with more women directors, for example, are more adept at uncovering root causes, making faster and better decisions, and holding CEOs accountable. We can consider it a success, then, that mounting pressure from market, legislative and other stakeholders has prompted boards in the United States and abroad to focus more on improving the gender and ethnic diversity of their board members, with measurable results: The 2022 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index states that as of 2022, 32% of all S&P 500 directors are women and 22% are from historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

While these inroads should be celebrated and continued, we also should not ignore that our efforts at boardroom diversity are still in a germinal stage — after all, the earliest legislation for diversity on boards dates back only to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. As advocates for diversity, we must ask ourselves whether the observable differences we have achieved in our boardrooms have also resulted in optimal diversity.

The answer is a tough one: Demographic variation (e.g., age, gender, ethnic differences across board members) might deliver optimal diversity, but sometimes this variation doesn’t quite hit the target, especially if our board members are largely drawn from the same social and professional networks. Achieving cognitive diversity means constructing a board of complementary knowledge, skills, connections, ways of thinking, backgrounds and more. However, a deeper look at why boards require diversity is needed, followed by clear and actionable definitions, examples and tools for achieving this kind of diversity.

Why Boards Need Diversity

Research on board diversity by organizations such as the University of Maryland School of Law has revealed seven principal reasons why boardrooms need to achieve a minimum level of heterogeneity.

- Talent. Talent is present in all population segments. Therefore, boards that ignore diverse population segments miss out on all possible talent.

- Market. Firms with diverse boards will be better equipped to market to and develop products and services for diverse populations.

- Litigation. Diverse boards have a perspective and sensitivity to anticipate and avoid legal exposure due to issues of discrimination.

- Employee relations. Diverse boards facilitate the creation of equitable company policies and signal that the firm is operating fairly, which boosts employees’ perceptions of justice, sense of satisfaction and productivity.

- Governance. Diverse directors tend to reflect a diversity of opinions and natural resistance to groupthink, leading to better quality decisions.

- Morality. Diversifying boardrooms is the right thing to do, given the diversity of the world’s populations and organizations.

- Social capital. Diverse directors enable the board and the firm to gain access to a wider pool of talent and other resources.

While each rationale has its proponents and critics, it is important to consider each of these as we evaluate whether our traditional definitions and approaches for achieving diversity are sufficient.

Traditional Definitions and Approaches to Diversity

Historical and formal definitions and efforts related to diversity to date have centered on gender and race. Age diversity also has received more attention in recent years, given pressures for social and digital transformation across industries. This focus is not unfounded, as diversity is still lacking on corporate boards. The tendency for boards to lack ethnic, gender and age diversity has earned them the label of being, as Risk Management once called them, “pale, male and stale.” Therefore, when executive teams or boards face internal or external pressure for more diversity, the search primarily begins for a female director, with fewer boards looking for directors from other underrepresented groups.

However, some caution is warranted in adopting a focus solely on demographic diversity, especially if the reason for doing so is to achieve business- or market-oriented aims. Lisa M. Fairfax, American legal scholar and Presidential Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, noted that making the argument for demographic diversity via any rationale beyond a moral one is just another means of commodifying underrepresented individuals. She further warned that these rationales can create unrealistic expectations regarding how diverse individuals may affect the corporate bottom line, potentially creating a backlash effect. Moreover, we need to acknowledge as we mature our understanding and approaches to boardroom diversity, that by themselves, variations in directors’ gender, ethnicity and age may be necessary but insufficient conditions for diversity. By ensuring that cognitive diversity also exists, we may, in turn, reap the range of diversity benefits boards need while avoiding the potential backlash noted by Fairfax.

Advancing Our Understanding of Diversity

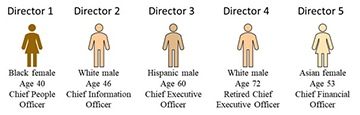

Optimal diversity builds on demographic diversity by additionally ensuring that diversity of thought is present. Consider the makeup of the following board:

At first glance, this appears to be a highly diverse board. The problem is that this selection ignores the issue of cognitive diversity, which is attained by achieving complementarity across directors in how they think about, understand and respond to the world. Philip Johnson-Laird, philosopher and former professor of psychology at Princeton University, used the term “mental models” to describe these ways of thinking and responding. Assembling a board of complementary mental models across directors is essential because every mental model — by definition, an idiosyncratic and subjective simplification of reality—is inherently limited.

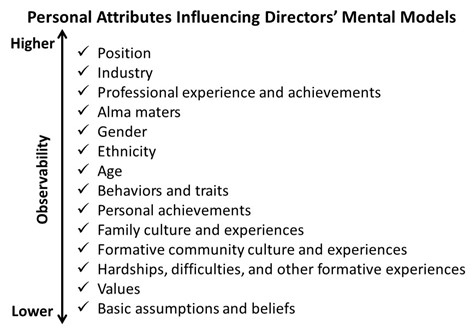

The challenge is that many personal attributes influence each director’s mental models, and these vary in terms of their observability:

When we reexamine the board in light of these personal attributes — apart from gender, age, ethnicity and position — we discover that all the directors grew up in the northeastern United States in affluent neighborhoods and attended Ivy League universities to earn their bachelor’s and MBA degrees. Most of them also started their careers at major consulting firms before joining Fortune 500 companies.

With this lens, a much different picture emerges. While this doesn’t mean that well-qualified diverse candidates should be eliminated from consideration, more attention could be given to the formative experiences that shape directors’ mental models and worldviews.

To help boards achieve optimal diversity, I suggest building on their demographic diversity by considering diversity in three additional areas.

- Human capital. Complementarity of the directors’ professional positions, industries, experiences, achievements, skills and knowledge.

- Social capital. Complementarity of the directors’ personal and professional networks of relationships and organizational affiliations.

- Cultural capital. Complementarity of the directors’ personal attributes, stemming from formative personal, family, community, academic, extracurricular and work experiences. This source of capital influences other sources of capital.

What Boards Can Do Now

Uncovering and examining these three sources of diversity requires careful approaches to maintain appropriate sensitivity to candidates’ privacy, while more fully understanding who they are and what they can bring to the board. In general, boards need to enact four tactics to create optimal diversity.

- Examine your existing board. Analyze your existing board members’ competencies in the three areas of human, social and cultural capital using self-assessments, 360-degree assessments and objective measures. Aggregating this information across the directors produces an assessment of the board’s collective capital.

- Create your needed competency profile. Your board requires a certain profile of competencies based on the environmental conditions, industry trends, stakeholder demands, strategic objectives, business needs and growth goals facing the firm it is governing. Using these inputs, create your board’s ideal competency profile.

- Identify your board’s specific diversity needs. Using your board’s assessment of collective capital and ideal competency profile, identify areas of complementarity and redundancy. Even more critically, identify gaps in the board’s collective capital. These gaps are called “structural holes” and lead to both risk and missed opportunity. These structural holes also reveal your board’s specific diversity requirements. Filling these gaps can help you gain critical access to new, nonredundant information and resources.

- Locate needed candidates. Use the diversity requirements you identified to create a competency profile that guides recruitment of additional members. If you have difficulty finding diverse available directors (a common liability of lacking diversity), third-party resources may help you access a vast pool of qualified diverse candidates.

Do Diversity Differently

Increasing boardroom diversity is critical for a variety of moral, business, market and legal objectives. While women and people of color have made important inroads in securing more seats, we need to mature our understanding and approaches to diversity to best support underrepresented individuals in delivering the benefits touted by diversity advocates. In short, getting different results requires us to do things differently. Focusing on optimal diversity characterized by demographic, human, social and cultural capital is the next chapter in getting there.

Dr. Keith D. Dorsey is a thought leader and official member of the Forbes Business Council, a board member of Vimly Benefit Solutions and Pepperdine Graziadio Business School, and managing partner, U.S. practice leader of CEO & Board Services at Boyden, a global executive search and leadership consulting firm.